The development of "green" buildings that regenerate degraded urban environments is essential to building healthy, sustainable communities in the 21st century. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories, Berkeley, Calif., rooftops represent 15 percent to 30 percent of the total land area in major cities. As such, they present a tremendous opportunity for positive change as a key component of green building and sustainable roof system design.

There are two basic types of green roof systems: extensive and intensive. Extensive green roof systems range from 1 inch to 5 inches (25 mm to 127 mm) in soil depth, typically consist of mosses and herbs, and are built primarily for their environmental and economic benefits rather than public access. Intensive green roof systems require at least 1 foot (0.3 m) of soil depth, elaborate irrigation and drainage systems, and maintenance. Typically designed to be publicly accessible, intensive green roof applications feature trees and shrubs and often resemble city parks.

The multiple paybacks of green roof systems are far-reaching and involve a mix of public and private benefits, including the following:

Give them a reason

Green roofs can be above, at or below grade and typically involve a system of lightweight growing media, root-repellant layers, filter cloths, a drainage layer and a variety of plants. Because of this intricate system, the initial cost of a green roof system often is at least twice as much as a conventional roof system. As a result, public incentives are required to help overcome the hurdle of higher upfront capital costs and help the public recognize the tangible, quantifiable economic values green roof infrastructure can bring to a community. By providing incentives, public institutions also can leverage millions of dollars in annual private roofing investments and turn unexploited, underused roofscapes to public good.

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, Toronto, is a membership-based association of public and private organizations working to build a multimillion-dollar market for green roof systems in North America. The organization advocates an approach centered on the development of cost-effective incentives for green roof system implementation based on tangible public benefits. Following are ways in which the organization is helping cities implement green roof infrastructure through direct and indirect public incentives rather than the more traditional regulatory approaches.

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities advocates public incentives to stimulate the market in lieu of regulatory requirements because regulatory requirements unfairly would shift the burden of additional capital costs fully onto building owners and developers. In most cities, this approach also would likely meet strong political resistance.

Furthermore, evidence from German policymakers (as published in the German roofing magazine Das Dachdecker-Handwerk) suggests regulatory approaches can result in green roof systems prone to neglect in contrast to voluntary, incentive-based approaches that result in better-maintained roof systems. The combination of incentives and regulations is a cornerstone of the German green roof industry.

Challenges

One key challenge associated with establishing public incentives is securing the cooperation required from vertically structured municipal departments. Often, the policies, programs and operational functions of these departments do not support, acknowledge or link to one another. As a result, the lines of communication are not optimal, making for a difficult policy-development process.

For example, a typical city parks department offering incentives for improved access to recreational green space often has little to do with a public works department, whose concern lies in storm water management, associated sewer overflow and flooding problems. But intensive green roof systems can address both issues.

Given that establishing a green roof infrastructure incentive program can improve multiple aspects of city life, it is important cities establish open, cooperative, interdisciplinary processes that reach across departmental divides and achieve a more holistic evaluation of the costs and benefits of public green roof system investment. Essentially, to gain a realistic representation of the value public green roof system investment can provide a community, green roof supporters must work to identify and link the tangible benefits found in such areas as storm water management, energy efficiency, reduction of urban heat islands, air-quality improvement and additional urban green space.

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities has found, through developing and delivering workshops designed to train local professionals and establish local market research and policy development processes, that tangible, measurable public benefits vary considerably among communities.

For example, cities such as San Francisco; Portland, Ore.; Regina, Saskatchewan; and Vancouver, British Columbia, are not terribly concerned with air-quality problems associated with urban heat islands. Such cities are more interested in green roof systems for their storm water management and related flooding and fishery conservation benefits. Other cities, such as New York and Toronto, face a broader range of environmental issues that can be fully or partially addressed through the widespread use of green roof systems on public and private buildings.

The tools or policy measures available to cities for green roof system investment also vary. For example, some cities have storm water management fees that enable them to reduce such fees in support of green roof systems. An incentive based on increased density for developers installing green roof systems is less likely to work in a city that is in a period of decline compared with one under development pressure (such as Portland or Vancouver). Understanding the unique challenges facing a community and analyzing the policy tools at hand is a key step in helping policymakers and other interested parties establish effective public incentives for green roof system implementation.

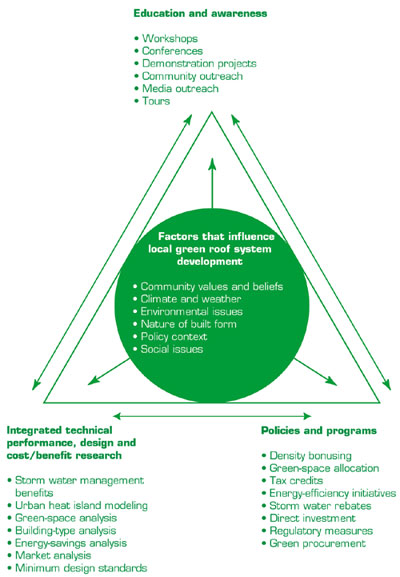

Figure 1: Holistic local green roof infrastructure development model

Figure 1 outlines a holistic local green roof infrastructure market development model. The three components at the tips of the triangle (education and awareness; integrated technical performance, design and cost/benefit research; and policies and programs) are the basic components of local green roof infrastructure development. The components are interdependent and self-supporting as indicated by the arrows. Each is influenced by local social, environmental and economic circumstances as indicated by the circle in the middle of the triangle.

To derive maximum benefit from green roof infrastructure, each community should consider assessing specific situations and exploring the three basic components through the process described in Figure 2.

Local market development

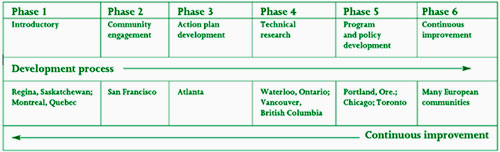

As discussed earlier, the benefits of green roof infrastructure and types of incentives that will yield the greatest benefits require communities to undergo a research and development process. This is a process in which a number of communities already are actively engaged (see Figure 2). The process typically involves a number of key phases, each of which is described in the following paragraphs.

Figure 2: Green roof infrastructure development process in selected communities

Phase 1 involves raising green roof system awareness via brief presentations to industry stakeholders, policymakers and nonprofit organizations. Typically, there are one or more green roof system supporters in a community who work to initiate this process.

Community engagement (Phase 2) comes next and involves working strategically with community leaders to organize a workshop aimed at accomplishing the following key objectives:

Phase 3 involves developing and implementing an action plan often based on information gained during the second phase. This may include the following:

In Phase 4, compiling technical performance data on a citywide scale can generate information that can be translated into public investment. Some key elements of this phase may include the following:

In addition to evaluating the various economic benefits available as a result of green roof system investment, Phase 4 also can be used to help policy-makers decide what type of design standards they want to specify for a building owner or developer to qualify for any given incentive.

Phase 5 involves translating technical research data into potential policy options. This will help determine the level of investment required to launch a green roof system market. The nature of any investment will vary from community to community but generally involves a mix of public and private funding. This may include public tools, such as how green roof systems relate to minimum regulatory requirements for green space, tax credits, energy-efficiency incentives, storm water fee reduction, direct investment and green roof procurement by government facilities.

Most local governments and related agencies have a number of these tools at their disposal and should combine multiple incentives for green roof system implementation. Given that many cities are strapped for funding, indirect incentives, such as tax-increment financing or density bonusing, may be more politically and economically feasible in the short term than direct investment.

In Germany for instance, where 14 percent of the country's low-slope roof systems are green, at least 76 municipalities offer a form of green roof system incentive.

More specifically, in some German cities, a rainwater tax is levied based on the amount of surface runoff a property generates. This tax has existed for a few decades and recently has been revised to offer tax breaks to building owners and homeowners who choose to install green roof systems. Discounts range from 30 percent to 100 percent depending on the city and often are used to pay for annual maintenance fees.

Another example of an established municipal incentive is in Portland, which now offers density incentives to private developers to encourage the installation of green roof systems as part of its floor area ratio bonus option.

The city has determined that when the total area of a green roof system is at least 10 percent but less than 30 percent of a building's footprint, each square foot earns 1 square foot of additional floor area. When the total area of a green roof is at least 30 percent but less than 60 percent of a building's footprint, each square foot of green roof earns 2 square feet of additional floor area. It also states when the total green roof area is 60 percent or more of a building's footprint, each square foot of green roof earns 3 square feet of additional floor area.

Currently, the density bonusing program affects about 5 percent of the city's total area.

Finally, Phase 6 involves assessing the effects of policies and efforts designed to improve the climate for green roof infrastructure implementation. For instance, existing incentives may be insufficient to achieve the desired number of green roof system installations and may have to be modified at a future date.

Phase 6 also should involve a technical assessment of the effects of green roof systems in specific areas of interest, such as storm water management.

Once communities have reached Phase 6, they may wish to revisit Phases 4 or 5 to explore other incentive options.

Planning for the future

Green buildings are essential to the development of sustainable, healthier communities, and green roof infrastructure is an important component. The steps outlined in this article can help community leaders learn from those already developing a green roof infrastructure market. In turn, the professional experience gained can help reinforce the work of other community leaders and, as a result, help North American cities become more sustainable.

Steven Peck is founder and executive director of Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, Toronto.

COMMENTS

Be the first to comment. Please log in to leave a comment.