The idea of servant leadership has gained popularity during the past few years, launching a variety of books about how to unleash the power of employees through adherence to fundamental moral and spiritual values. Touted as a new way to combat overreliance on management practices that place profit seeking over the well-being of employees, servant leadership shuns so-called traditional authoritarian models for getting things done and promotes, in part, the following simple set of guidelines:

- Making your expectations for results clear

- Asking employees what they need to do a good job

- Helping them secure necessary resources, training and other support

- Removing barriers

- Recognizing successes and coaching failures

- Staying out of the way

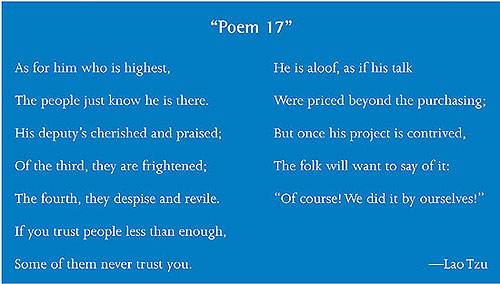

Although these edicts have merit and may well deliver results, they tell only a fraction of the story of leadership. The leadership philosophy that illustrates servant leadership's place in managerial practice was more fully developed 3,000 years ago by Lao Tzu in Tao Te Ching. His "Poem 17" captures the complexity of leading people and need to offset servant leadership with authoritarianism (see sidebar). With too much control, a task stultifies as creative processes and problem-solving give way to budgets and schedules and punishments meted out for failure. With too much empowerment, a vision loses clarity, setting organization goals adrift with selfish motivations. True leadership calls for the right practices at the right time. The following represents my modest interpretation of the concepts of Lao Tzu's "Poem 17."

1. Control. Lao Tzu speaks of the need to strategically manage organizational hierarchy. The higher a leader's position, the more likely he will enjoy reverence and affection. However, lower managers work closest to support staff and mete out demands, deadlines and, in some cases, demerits. Good leaders strategically use hierarchy to maintain their appearance as servant leaders while preserving their ability to make critical—and sometimes difficult—mandates.

2. Trust. According to Lao Tzu, effective leadership, whether authoritarian or servant, relies on encouraging and earning employees' trust. Authoritarian management practices can feel overbearing and disrespectful if employees do not understand the need for them. Trust built through communication and adherence to predictable principles helps employees tolerate authoritarian directives. It also allows a leader to mitigate leadership-by-edict, giving employees room to perform outside the scrutiny of close supervision.

3. Empowerment. Lao Tzu speaks of the practice of servant leadership, supporting the notion that sometimes a leader's voice need not be heard directly, and instead, through his support and unobserved actions, people can accomplish great works that unleash employee creativity. In the end, employees often have full ownership of their achievements.

Lao Tzu seems to argue leaders cannot simply choose to command or nurture their people. Different situations call for different styles. Although current servant leadership books have it half right, perhaps we should leave it to an old master to explain how it should be done.

Karen L. Cates is a professor of management at Monmouth College, Monmouth, Ill.; teaches executive courses for Evanston, Ill.-based Northwestern University's Kellogg School of Management; and consults clients about leadership and decision making.