While teaching one of NRCA’s Qualified Trainer Conferences recently, we heard someone exclaim: “I’m definitely not going to just stand there and let him make a mistake!”

The students were working in two groups when we overheard the loud voice coming from one group. The members in the other group stopped what they were doing and looked over to see an instructor and participant energetically discussing the pros and cons of allowing trainees to make mistakes.

The participant was an excellent, experienced roofing professional. He had risen to senior superintendent during a successful 30-year career. Allowing his trainees to make mistakes was so untenable to him, he likened it to suggesting children put their fingers into electric sockets to teach them about electricity. As other participants agreed with him, we discussed it.

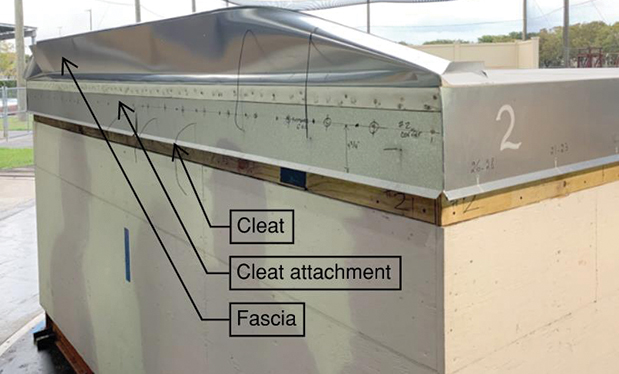

We explained intentional training means having time and space to conduct skills training—it’s not something that happens during active installations where production is the goal. Allowing trainees to make mistakes means having mockups available in the shop and materials available for trainees to ruin.

Intentional training is one of the most efficient, effective ways to increase production while improving employee retention.

Benefits of allowing mistakes

Mistakes can be productive and desirable in the proper context. Exposing learners to challenging situations and allowing them to make mistakes and spend time figuring out why the mistakes were made means trainees actively engage in problem solving. This type of learning increases retention, and mistakes learned during training are less likely to be made when it matters most.

The following anecdote exemplifies the importance of making mistakes.

While working in an unfamiliar town, the driver of a roofing crew takes a wrong turn on the way to the job site. He forgot his phone in the hotel room and couldn’t check directions, so he meanders his way through the town based on what he remembers from a previous trip. He sees the sun rising and knows the job site is on the opposite side of town. He also recognizes a restaurant, so he can orient himself. He makes a few more wrong turns before finding his way to the correct address.

The next day when the crew is on their way to the job site, they encounter a new and unmarked detour. Thanks to the driver’s unintended drive through many back roads the previous day, he aptly navigated his way to the job site and the crew arrives 15 minutes earlier than anyone else.

NRCA has developed its Qualified Trainer Conference, a state-of-the-art classroom and two-day hands-on educational program that empowers employees to become expert trainers who can educate others to develop a strong workforce. Qualified trainers become equipped to successfully train employees on-site without loss of productivity. To learn more, contact Jon Goodman, NRCA’s roofing subject matter expert, at jgoodman@nrca.net.

Critical thinking

The moment the driver realized he took a wrong turn, his brain needed to process things differently than when he was following a repetitive pattern. He had to think about what he knew and did not know at that moment.

He had to consider his options as well as his resources. He was not in any danger, so he could relax. He could see where the sun was rising, so he knew the job site was on the opposite side of town. And he recognized a landmark—the restaurant—to help guide him.

Critical thinking is being able to objectively assess a situation to make decisions. In this case, the driver was able to quickly assess the facts and arrive at the job site without too much stress or delay. And the next day, he used what he learned from his previous mistake to make his way through the detour.Greater engagement

The driver in our example had to pay keen attention to his surroundings, street signs, and any information he had or was given. The only way to find one’s way through unfamiliarity without exact step-by-step guidance is to focus on making the best decisions possible. Because of his focus during uncertainty, the driver recalled what he experienced and was able to access that learning the next day.

Retention

Retention is enhanced through making decisions in the face of uncertainty and during the process of fixing mistakes. The more someone needs to think, consider options and make choices, the more learning will be retained.

If the driver turned down a dead-end street or ended up going the wrong way on a one-way street, not only is he more likely to remember to go the right way the next time but he also will remember why he needs to go the right way. He will find his way out of tricky situations and solve problems until he ends up where he needs to be. The act of problem solving solidifies information.

Confidence

Allowing a person to figure out how to do something in the face of many options increases confidence. However, we want to stress trainers always should explain and demonstrate skills thoroughly before expecting trainees to try skills.

For example, after a thorough demonstration and explanation of a pipe boot installation, a trainee should be allowed to install one without assistance—forcing him or her to think about the steps and the several ways he or she might not do it exactly right.

Then, after completing a skill, trainees always should be encouraged to assess their own work regarding whether their installation is on par with the trainer’s installation and determine discrepancies. The process of figuring things out rather than just doing what a trainee is told is deep learning.

Dedicated trainers

Having a dedicated trainer on staff is one key ingredient of successful training. Whether a trainer is full- or part-time, productive training requires someone who is responsible for setting up intentional training. This kind of training also must include time separate from productive installation work.

Often, roofing companies default to training on roofs during active jobs. Foremen are tasked with most of it while simultaneously managing jobs and crews in locations where trainees absolutely cannot make mistakes. This is a setup for frustration and stress: Foremen are pulled in too many directions, and new employees feel inadequate.

The best training system in the U.S. is in the military. Boot camp, also known as basic training, comprises six to 12 weeks of nothing but training conducted by training specialists on dedicated training bases. According to the Army’s website, about 90% of recruits complete boot camp and go on to be soldiers. These soldiers are from the same pool of young adults we often accuse of not wanting to work hard or having no work ethic.

No one expects contractors to offer 10 weeks of hard-core training. However, 10 hours of full-on training by dedicated trainers in a specific training space could make all the difference.

What do dedicated trainers do?

Someone who has the wherewithal to focus intentional energy on establishing good training will take the time to clearly define several things:

- Learning outcomes. These are explicit intentions for what each trainee will be able to do as a result of his or her training—overall and for each individual session.

- A consistent schedule. Developing a training schedule—over time and within each individual session—maximizes efforts.

- A systematic approach to each skill. Allow trainees time to understand what they are learning, attempt skills on their own, evaluate mistakes and repeat efforts until they achieve consistent success.

The value of dedicated space

Naval Station Great Lakes, Great Lakes, Ill., is where all U.S. Navy boot camps occur. It has a massive destroyer simulator called the USS Trayer. Designed by award-winning Hollywood set designers, it allows trainers to put recruits through the paces of various skills and situations in a realistic setting but without danger. Many industries use simulators so employees can learn how to do their jobs without drowning at sea, crashing planes or being lost in space.

Although the scale and hazards are different, mockups in a corner of a roofing shop serve much the same purpose as the USS Trayer. Mockups are made for practice. Once a task is complete and evaluated, it can be torn off and tried again.

Roof system installers can learn and practice new skills without many of the hazards they will experience on a rooftop. They also are not under the pressure of being on an active site where accuracy is critical and time is of the essence.

A dedicated trainer can allow a trainee to work alone because he or she is not surrounded by job-site pressures and will think more clearly to experience more successes and learning.

The only time a trainer should intervene is when a trainee is engaging in hazardous behavior without taking proper precautions. If a trainee is not in danger, forgetting PPE is a valuable debrief conversation. But if the trainee is not wearing gloves and starting to work with chemicals, a trainer needs to intervene before the trainee begins the task. Safety always is paramount to learning.

Taking it to the job site

Of course, the aim is not to remain on a mockup. Trainers prepare employees to implement their skills into their jobs. Ideally, a trainer will be able to take trainees onto job sites and work with them there, helping them to integrate mockup skills and mindsets into real roofing work.

Mistakes on an active job site might not be received with the same patience and tutelage of a training session. However, an installer used to recovering from mistakes during mockup training will be more equipped to manage situations more effectively than an installer who only knows how things are supposed to work. Intentionally trained workers will use their tools of critical thinking, experience and confidence to regroup and figure out how to fix mistakes.

Installers with intentional training skills also will be better poised to apply their skills in various and unique situations and from one job to the next.

Allowing trainees to make mistakes not only develops skills but problem-solving capacities, and it does so in an environment that demonstrates respect for the individual and the learning process.

JARED RIBBLE is vice president of certifications, and AMY STASKA is vice president of NRCA University.