When two dissimilar metals come in contact, such as when metal fasteners are used to attach metal flashings or accessories, one of the metals has an increased potential to corrode. This is referred to as galvanic corrosion, and there are steps roof system designers can take to prevent this from occurring.

Galvanic corrosion

When two dissimilar metals come in contact and are exposed to a common electrolyte, one of the metals can undergo increased corrosion while the other metal can show decreased corrosion potential. Any solution containing water can be an electrolyte. Rainwater, dew and condensation are electrolytes because they contain dissolved ions from common environmental conditions. In comparison, seawater is a more conductive electrolyte and, therefore, more corrosive because of its much higher concentration of dissolved salt ions.

Because galvanic corrosion can occur at a high rate, it is important a reliable means be used to identify dissimilar metal combinations that exhibit galvanic corrosion potential.

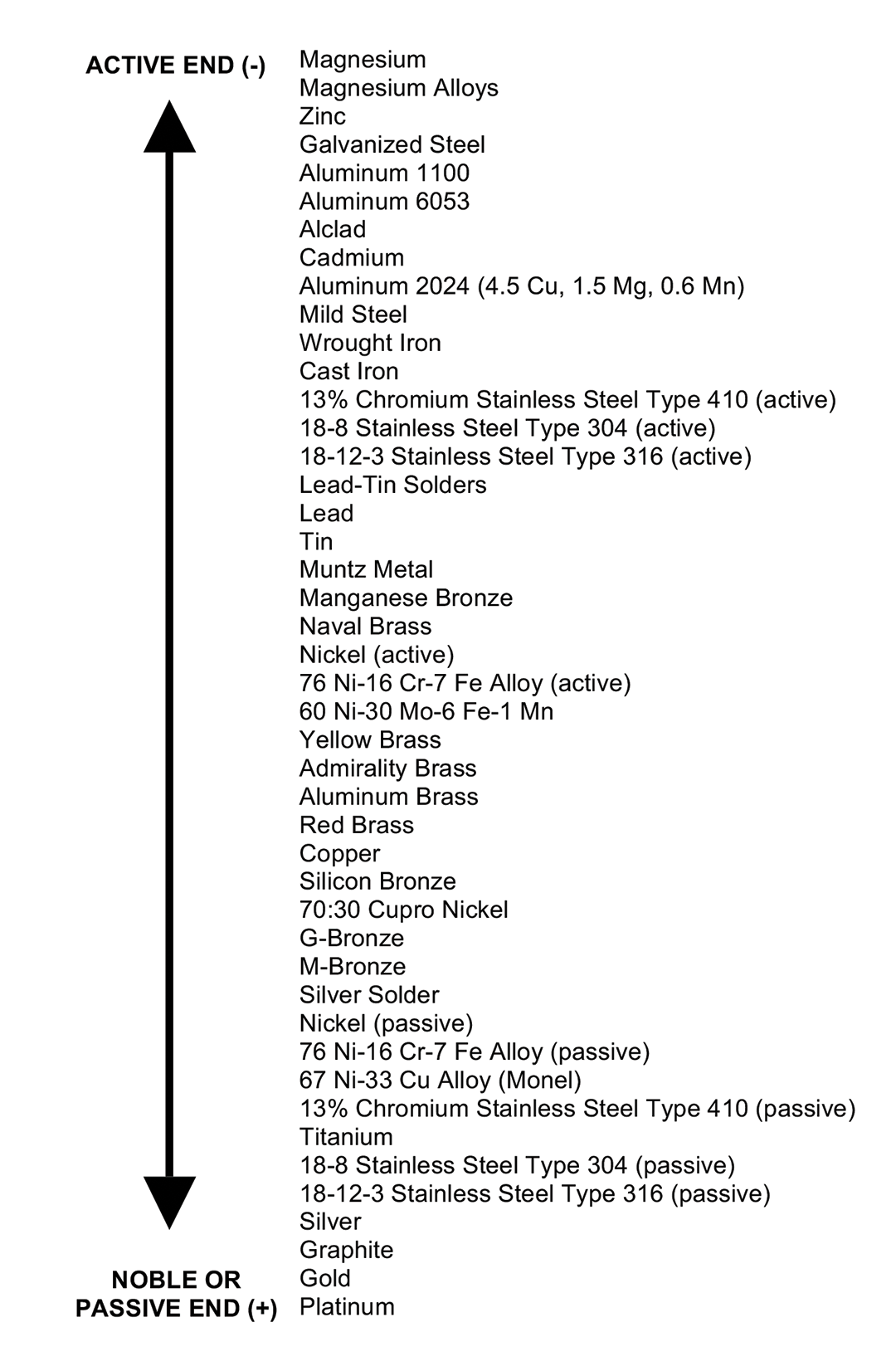

A method commonly used to predict the effects of galvanic corrosion is to develop a galvanic series by arranging a list of metals in order of observed corrosion potentials. One such galvanic series based on metals exposed to seawater is shown in Figure 1. This galvanic series is formatted with the most active (electronegative) metals at the top and the most noble, or passive, (electropositive) metals at the bottom.

Figure 1: Galvanic series of various metals

Figure 1: Galvanic series of various metals

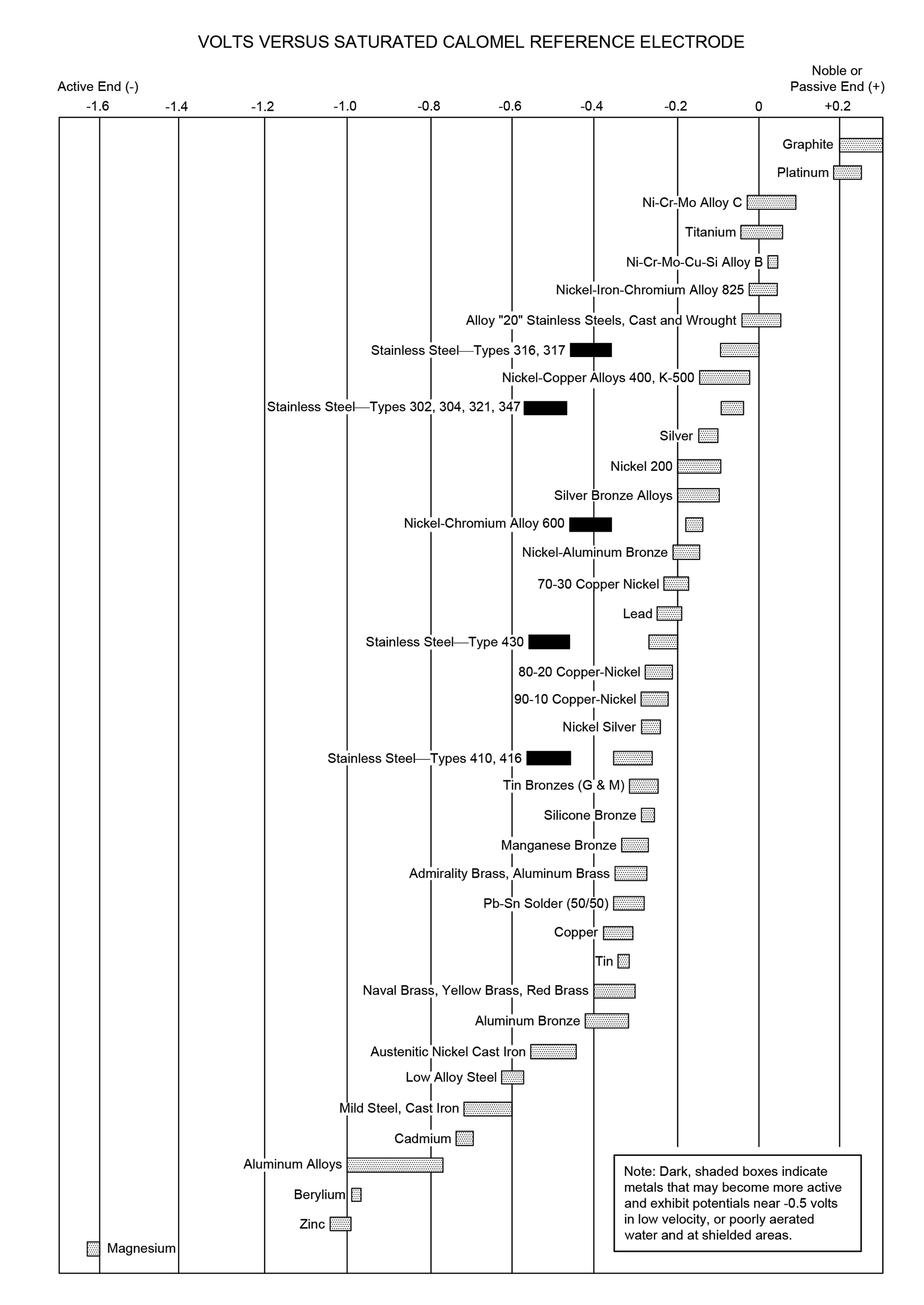

A more complex galvanic series is provided in Figure 2. This series acknowledges most metals have ranges of potentials based on their specific compositions, which are depicted in this series using bars. Some metals, such as tin, have relatively narrow potential ranges, while other metals, such as aluminum alloys, have notably wider potential ranges. This galvanic series is presented with the most active metals on the left and most noble, or passive, metals on the right.

Figure 2: Galvanic series of various metals (adapted from a similar table in ASTM G82)

Figure 2: Galvanic series of various metals (adapted from a similar table in ASTM G82)

Generally, the more active metal (anode) tends to undergo increased corrosion while the more noble, or passive, metal (cathode) tends to undergo reduced corrosion.

Usually, the farther apart two metals are in a galvanic series, the greater the driving force for galvanic corrosion becomes.

NRCA recommendations

NRCA recommends roof system designers consider galvanic corrosion and consult a galvanic series for the specific metals being considered when dissimilar metals will be involved on a project.

Also, designers should consider local environment, the metals’ anode to cathode area ratio and runoff from incompatible metals. For example, 300-series stainless-steel fasteners are successfully used with galvanized sheet metal though stainless steel is far removed from zinc in the galvanic series. However, the reverse presents a problem because it combines a small anode with a large cathode.

Similarly, water runoff from a copper gutter into an aluminum downspout will result in premature failure of the aluminum downspout. On the other hand, an aluminum gutter draining into a copper downspout would not have the same effect (except at the connection point of the two metals).

Additional information about dissimilar metal contact and considerations about how to minimize corrosion potential is provided in Chapter 1—Guidelines Applicable to Metal of the Architectural Metal Flashing section of The NRCA Roofing Manual: Architectural Metal Flashing and Condensation and Air Leakage Control—2018.

Mark S. Graham is NRCA's vice president of technical services.

@MarkGrahamNRCA

This column is part of Research + Tech. Click here to read additional stories from this section.